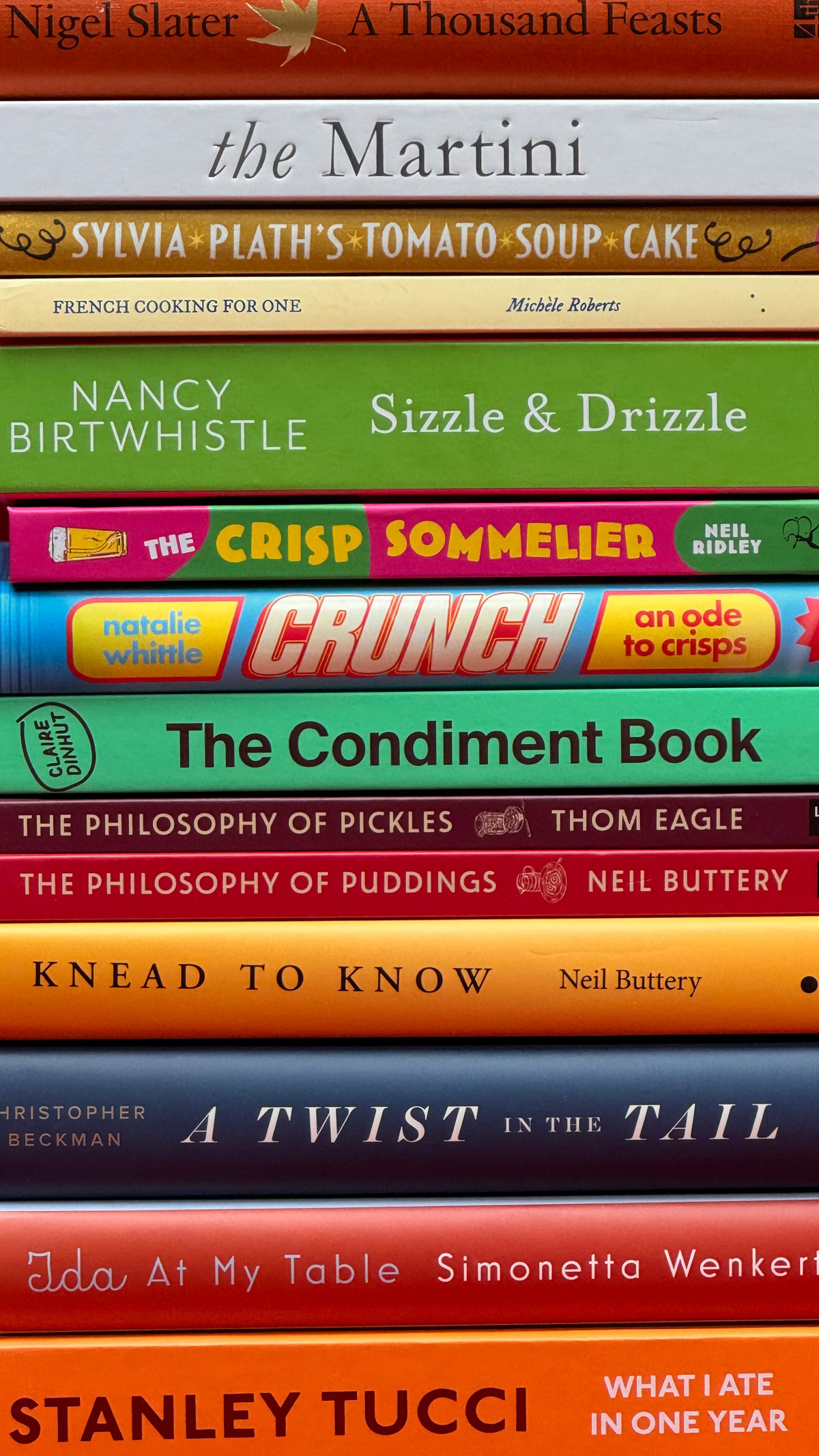

While I obviously have complete editorial freedom insofar as choosing which books get picked for CookbookCorner — it’s only me here, after all! — I do face some constraints. If I were a coder, no doubt I’d find a way around this but, as it is, the format is unyielding. Not only does it insist upon a recipe, but once this recipe is input, a space automatically opens up for its accompanying photograph. No picture: no dice. As a consequence, however much I love them, books with unillustrated recipes and those about food but without recipes at all, are cruelly barred from CookbookCorner. The other major constraint is that of space: there’s room for but one title a week; all other contenders, however deserving, must fall by the wayside. It’s true that I often spotlight those that fail to make the cut, whether for reasons of space or conformation, by giving them a shout-out on social media, but as a one-off Christmas treat, the tech-team has found a space for me to run riot in, all rules ripped up, so that I can bring you a list of stocking fillers for the food-focussed! All the titles mentioned have been published this year, and there are quite a few, so I should stop wittering on and just get on with it. But first I should quickly give you a link to all the CookbookCorners of 2024 so you can consider these, too before choosing what you might give to whom.

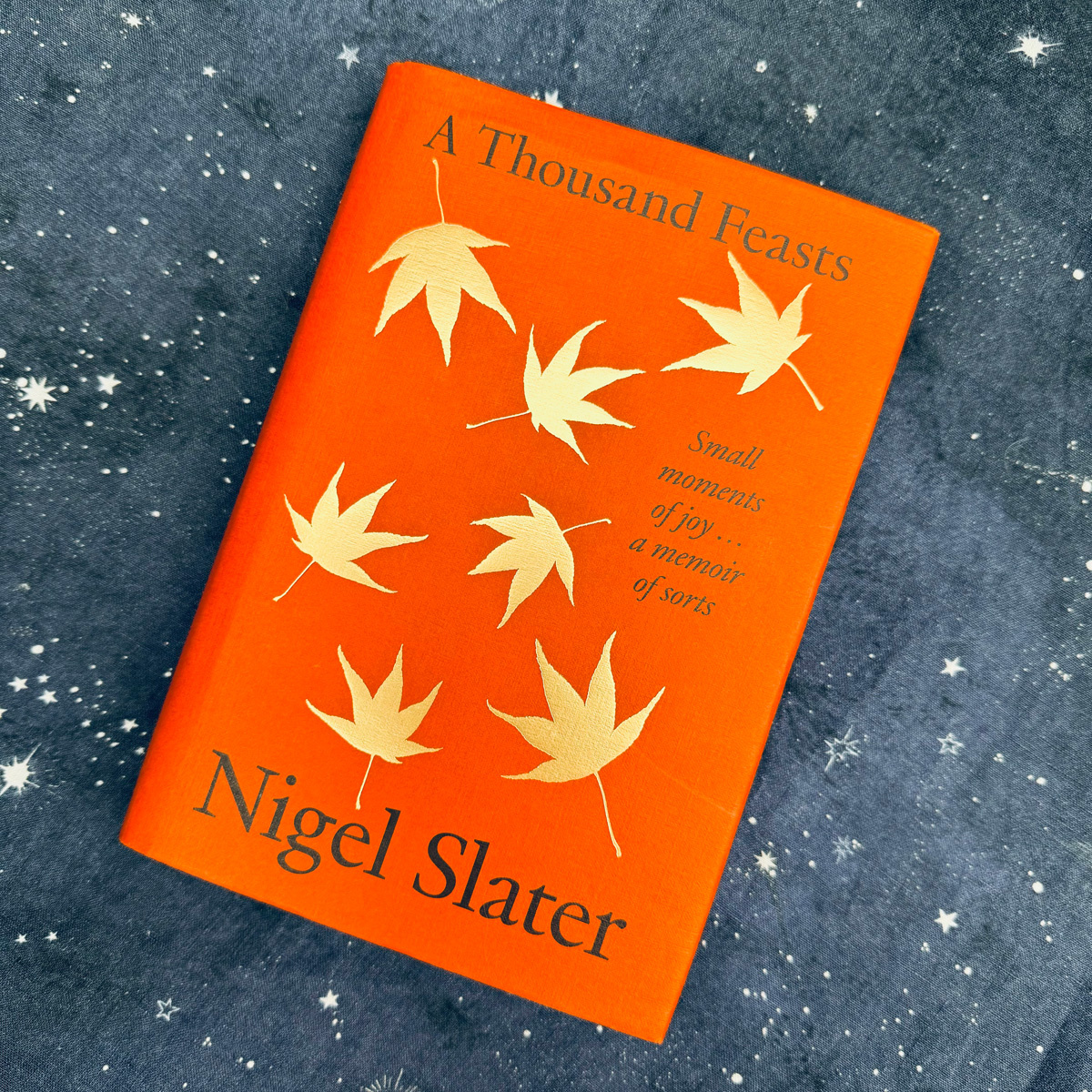

But where to start? With Nigel, of course. A Thousand Feasts by Nigel Slater (published by Fourth Estate) is subtitled “Small moments of joy… a memoir of sorts” and is everything you need it to be — and more. Culled from Slater’s kitchen notebooks over the years, “an untidy bundle of haphazard observations”, according to his modest description, that come together to form something between a diary in collage form and a delicate yet vivid chronicle of a particular sensibility, a sensibility we have grown to trust and draw comfort and inspiration from over the years. “The thread that binds them”, he writes about the entries gathered in the notebooks, and brought to us in these pages, “is their spirit, a need to keep a written record of the good things, memories of meals shared or eaten alone, of journeys and places, events and happenings, small things that have given pleasure before they disappeared…They are, almost without exception, moments of quiet jubilation: a ripe mango eaten in a rainstorm; the smell of incense in a temple or the sound of footsteps on the stone floor of an abbey. They are chronicles of quietness and calm, busy days in the kitchen and sensuous afternoons in the garden.” His evocative, exquisitely-noted observations are a balm for life: a prose-poem for eaters and a spiritual companion for thoughtful cooks.

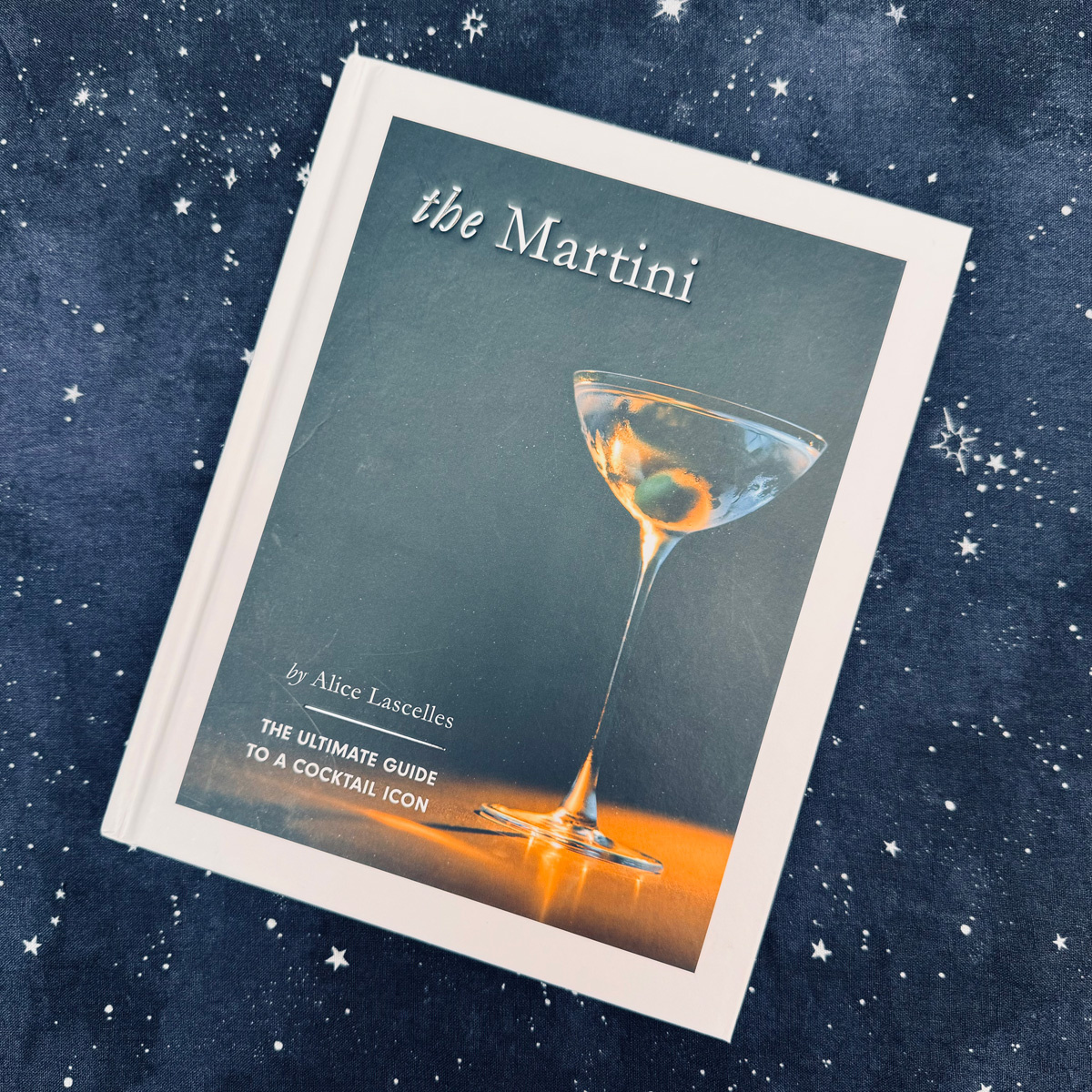

My next pick, in the spirit of December’s Saturnalian anarchy, isn’t even a food book! The Martini: The Ultimate Guide to a Cocktail Icon by Alice Lascelles (published by Quadrille). I’m pretty trad when it comes to martinis (notwithstanding that I go for vodka not gin, and must confess to including — it was a phase that I cannot completely regret — a retina-searingly lurid apple martini in one of my books) so I didn’t think I needed a whole book on the subject. It turns out I absolutely did! Indeed, I have developed something of an obsession with it and, since its publication in September, have not been able to stop myself pressing it on people. I think I must have bought 5 copies to give to friends as a present, and that doesn’t even take in Christmas yet. The writing is crisply clever but at the same time so warmly engaging and witty, and it is such a beautiful book, too. I know from experience how difficult drinks can be to photograph, especially one after the other, but Laura Edwards has captured every martini exquisitely, each photo an atmospheric work of art. These images would be perfect as a framed set of prints. And actually, I would so love to turn the cover image of a classic dry martini into a kitchen blind! I couldn’t love this book more.

Next comes another title I’ve already given multiple copies of as presents: Sylvia Plath’s Tomato Soup Cake, A Compendium of Authors’ Favourite Recipes (published by Faber & Faber), with a foreword by the always-wonderful Bee Wilson. It’s the perfect book, compiled with elegant wit, designed with charm and brio, and Joe McLaren’s illustrations are a joy, as you can see from the cover. It’s small — the size and shape remind me of the Ladybird books I read as a child — but the huge pleasure it yields is disproportionate to its modest dimensions. Entries include Ian Fleming’s Scrambled Eggs; Vladimir Nabokov’s Eggs à la Nabocoque; Joan Didion’s Mexican Chicken; Georges Simenon’s Fricandeau à l’Oseille (veal forcemeat with sorrel); Barbara Pym’s Marmalade; Enid Blyton’s Cherry Cake; Truman Capote’s Cold Banana Pudding; Nora Ephron’s Bread Pudding; George Orwell’s Plum Cake; and, of course, the title recipe given to Plath by her mother, for a spiced cake containing a can of condensed tomato soup. You might not want to eat all the recipes, but that is far from being a condemnation. Indeed, I think my favourite entry might be the most revolting — Noël Streatfield’s Filets de Bœuf aux Bananas, which begins, winningly, with the words “I have to admit that I am normally a very bad cook” — though there is plenty of competition for this accolade. It’s a book to be given with glee and read with relish. Total bliss.

French Cooking for One by Michèle Roberts (published by Les Fugitives) provides a very different sort of pleasure: it’s an enduring delight for readers and cooks alike. And its old-school approach has nothing of the retro campness — enjoy it though I do — of Sylvia Plath’s Tomato Soup Cake. Roberts (author of, inter alia, Daughters of the House; Food, Sex & God; and, more recently, Colette, My Literary Mother) is a beautiful memoirist, reflective essayist, and novelist of the first degree. I actually first came across her writing in the early 80s, with the publication of her second novel, The Visitation, and have never understood why she hasn’t been more fêted. Half-French, half-English, and with an acutely tuned sensibility quite her own, this is her first actual cookbook. By “old-school approach”, I don’t mean that it is a curio or museum piece, but simply that she writes with the assumption that her readers can cook and want brisk but intelligent company in the kitchen (though I must assure you that her uncluttered recipes have just the rigour that’s needed for them to be followed comfortably) and that this notebook-sized collection, while it conveys a huge number of said recipes and much delicious information, contains not a single photograph.

The new edition of Nancy Birtwhistle’s Sizzle & Drizzle: Over 100 Essential Bakes, Recipes and Tips (published by One Boat) is also photo-free, but each recipe is printed with a QR code taking you to a video of the wonderful Nancy in her Lincolnshire kitchen making the recipe in question. I’m a huge fan of hers, and love her old-fashioned bakes and cakes, her welcoming twinkle, and her no-nonsense wisdom. This book is a treasure trove, containing advice invaluable for the seasoned baker and essential for the novice.

I have not one but two books on crisps (a subject very dear to me) to tell you about. First up, The Crisp Sommelier: The Ultimate Guide to Crisp and Drink Pairings by Neil Ridley (published by Bloomsbury), a perfect stocking-filler if ever I saw one. My own experience in this field has taught me that there is no better pairing than a packet of salt and vinegar crisps and a Campari Soda, but for more wide-ranging advice and expertise, I refer you to Ridley! Natalie Whittle’s Crunch: An Ode to Crisps (published by Faber & Faber) is both fascinating social history and a beguiling account of an obsession. I cannot do better than quote Felicity Cloake who, writing about this book, concluded with the words “I devoured it until the very last crumb and then licked the packet.” It’s a triumph.

Another area of vital concern to me all year round but especially at Christmas is addressed gloriously in the pages of The Condiment Book by Claire Dinhut (published by Bloomsbury) and which she begins emphatically by declaring “This is not a cookbook. I repeat, this is NOT a cookbook. Instead, think of this book as a flavour manual. It does, however, contain recipes and, though no photographs, is dotted with charming illustrations by Eloise Myatt, Siena Zadro and Katherine Zhang of Evi-O. Studio, along with informative and helpful charts giving guidance on ingredients and their possibilities. Dressings, dips, sauces, pickles and jams: all are covered in this bright and punchy powerhouse of a book, one that promises to be a proper friend in the kitchen.

Sour condiments and ferments are addressed in a rather different way in my next title for you: The Philosophy of Pickles by Thom Eagle, part of an ongoing series from the British Library. I have a rule about books by Thom Eagle: if he’s written it, I want to read it (and I refer you to earlier works, First, Catch and Summer’s Lease, as well). He’s an elegant writer and something of an obsessive, a combination that I’m always particularly drawn to. Not that you need to be a fellow fermenter to find intelligent companionship in the pages of this compact historical enquiry into pickles.

The food historian Neil Buttery also has a book out in the series this year, as he addresses The Philosophy of Puddings, and most delightfully, too. He is also the only author to have two titles in this round-up: the second being his joyfully informative Knead to Know: A History of Baking, which deserves equal commendation.

Sticking, for a moment more, with the joys of the single-subject focus, I must present to you Christopher Beckman’s A Twist in the Tail: How the Humble Anchovy Flavoured Western Cuisine (published by C. Hurst & Co), which wades deeply into the history, social and culinary, of the bacon of the sea.

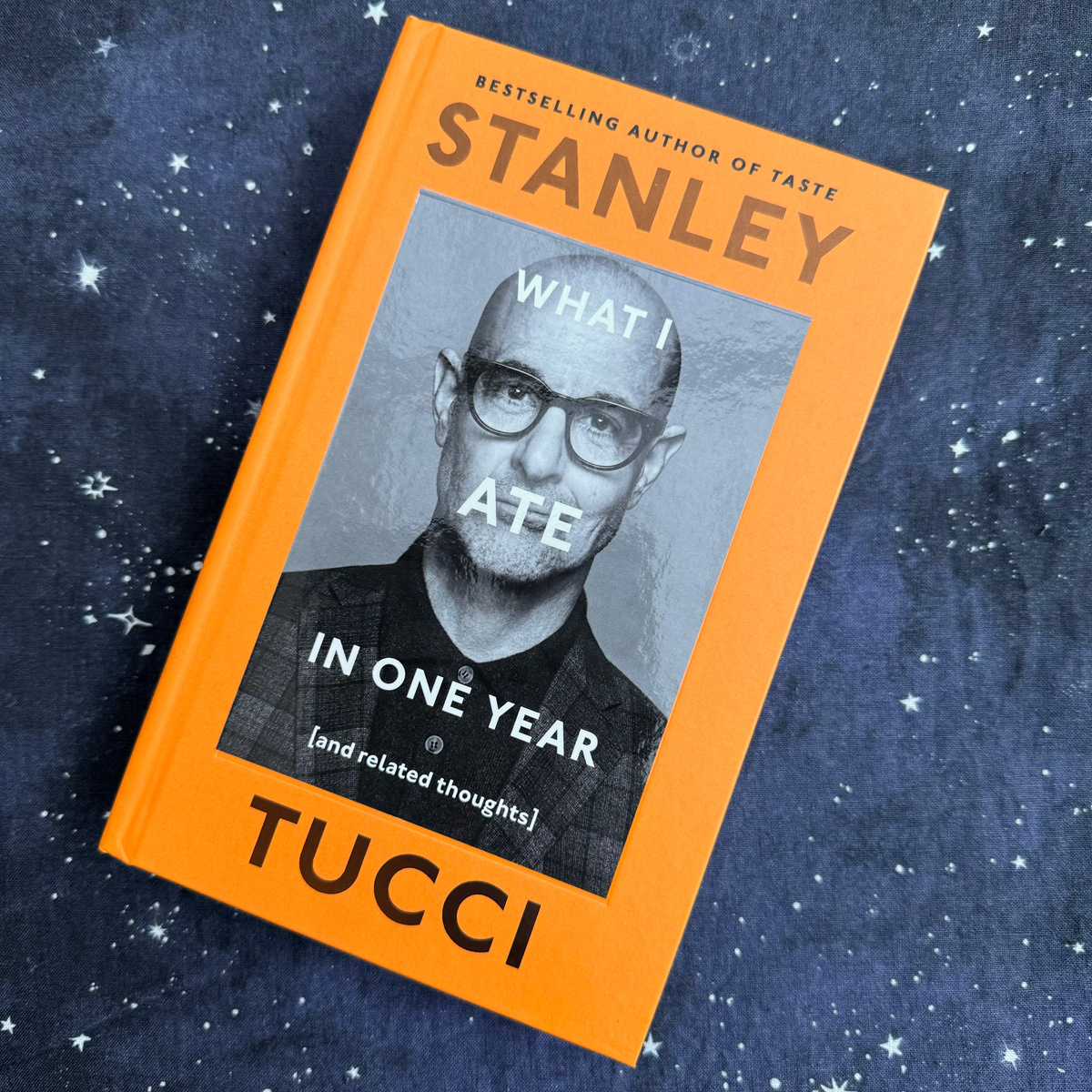

The last two books here provide food commentary of a more personal persuasion: Simonetta Wenkert’s Ida, At My Table: A Story of Family, Food and Finding Home (published by Bedford Square) and Stanley Tucci’s What I Ate in One Year (and related thoughts) (published by Penguin). I say ‘food commentary’ but, as we all know, to write about food is to write about life.